Km 8800-9670. San Jorge Gulf Basin.

Pico Truncado. Santa Cruz. 2018 © Leo Micieli

Pico Truncado. Santa Cruz. 2018 © Leo Micieli

Km 8800-9670. San Jorge Gulf Basin. May 23rd, 2018.

-Do you work in oil?

-No, I'd wish to...

A wish sprouts out from this short answer. But it rather seems an obsession inside of a wish, a hope of having a chance at last. This dialogue may occur in any place of the San Jorge Gulf Basin, and in each oil area. It's a recurring thought, like a leitmotiv in a movie, pointing the psyche of many who live here, or who are trying to. The goal is a salary much more higher than the average. A glimpse of abundance appears on the harsh patagonian horizon, but it's a narrow and viscous abundance, dark like a stormy sunset, or the fluid from which it comes. Sometimes the price is too high for the fulfilled wish.

It wasn't always like this here. Until the begining of XX Century oil was hardly considered by the Government. Coal brought from Great Britain, as dark as oil, supplied the energy on those years, while politicians and landowners looked after those interests. Neither Patagonia seemed to be part of the country. The slaughter carried out by the president Julio Argentino Roca razed the native communities, and in the remote and still undefined territory of the South there were only wind and steppe, which nobody cared about. History starts to change on December 13rd of 1907, when oil is finally found in the small town of Comodoro Rivadavia. Official History tells that while searching for water it began to emerge oil. Serendipity... But oil was sought since long time ago, and the usual meanness didn't allow to explore it.

In these circumstances Patagonia starts to integrate to the rest of the country, through the oil of the Basin, the largest Argentinian hydrocarbons producing region. The beginnings were not easy. Neither the present is. It's known: the resource, unlike the hope, is not renewed.

Perito Moreno. Santa Cruz. 2018 © Leo Micieli

Perito Moreno. Santa Cruz. 2018 © Leo Micieli

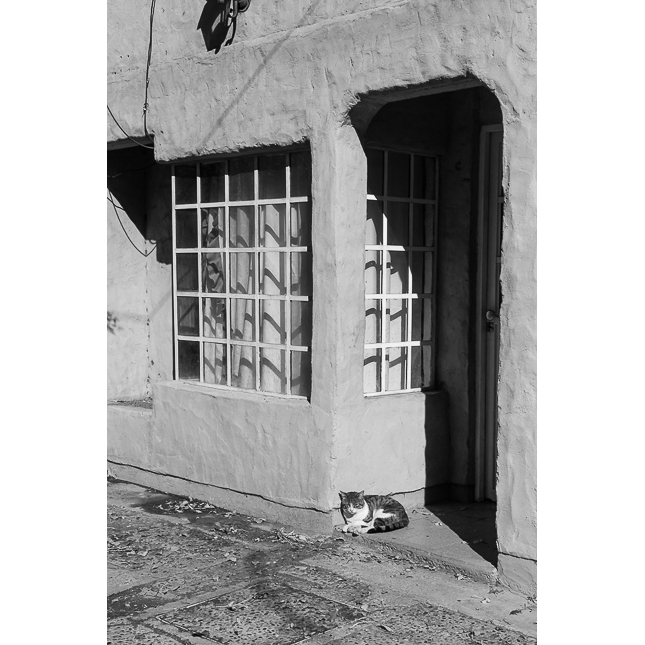

Autumn dyes the road and the surroundings on this stage of the trip. Perito Moreno goes in the mood of the season; the streets and the main avenue show an autumnal nostalgia on their buildings and trees. Many corners and old houses have signs on the walls telling about their historical value. A fleeting trip to other times, something that remains but it's no longer as it was. For moment the imagination places itself on the first decades of the XX Century, and that instant becomes eternal, like a short film from that age.

Perito Moreno. Santa Cruz. 2018 © Leo Micieli

Perito Moreno. Santa Cruz. 2018 © Leo Micieli

Perito Moreno. Santa Cruz. 2018 © Leo Micieli

Perito Moreno. Santa Cruz. 2018 © Leo Micieli

Perito Moreno. Santa Cruz. 2018 © Leo Micieli

Perito Moreno. Santa Cruz. 2018 © Leo Micieli

It's an oil zone, and also mining zone. In the Highlands of the Deseado gold and silver are extracted, so the town has, besides a stable population, a fluctuating population.

It seems that the basin is marked by resource-extraction activities.

Perito Moreno. Santa Cruz. 2018 © Leo Micieli

Perito Moreno. Santa Cruz. 2018 © Leo Micieli

Lake of the Swans. Perito Moreno, Santa Cruz. 2018 © Leo Micieli

Lake of the Swans. Perito Moreno, Santa Cruz. 2018 © Leo Micieli

Perito Moreno. Santa Cruz. 2018 © Leo Micieli

Perito Moreno. Santa Cruz. 2018 © Leo Micieli

Perito Moreno. Santa Cruz. 2018 © Leo Micieli

Perito Moreno. Santa Cruz. 2018 © Leo Micieli

The road begins to show the pumpjacks to one side and another, going up and down like birds looking for food under the ground.

A common factor in Patagonia is that part of the population was not born in the territory but in the "North" or Chile. Oil Industry also makes people to migrate which results in a wide pot of accents, customs and cultures living in the same place. The other side of the story has to do with the distance to the places of origin, the roughness of the weather and the quality of life, which not always are compensated by the higher salaries of those who work in the oil, something that is not taken into account and goes to the background. The sense of belonging and commitment with the places is low, it's not frequent to hear people talking about the link between them and the towns they're living in, except for their jobs.

Las Heras. Santa Cruz. 2018 © Leo Micieli

Las Heras. Santa Cruz. 2018 © Leo Micieli

Las Heras. Santa Cruz. 2018 © Leo Micieli

Las Heras. Santa Cruz. 2018 © Leo Micieli

Las Heras. Santa Cruz. 2018 © Leo Micieli

Las Heras. Santa Cruz. 2018 © Leo Micieli

Some years ago Las Heras earned the nickname of "city with the highest rate of youth suicides". Though the suicide rate is high, it's better to demystify and be careful such a delicate matter in which tags could lead to stigmatize the town rather than just indicate a situation.

A research was done and even a short documentary film was shot about this issue, but some say that it's not accurate and that the high rate of suicides corresponds to those occurred in public places. Beyond the accuracy of the data, suicides are a sad and concerning reality that often happens not only here but in many places of Patagonia, further North or South. There are many causes for this phenomenon, and they have to do with more than a hostile weather.

Las Heras. Santa Cruz. 2018 © Leo Micieli

Las Heras. Santa Cruz. 2018 © Leo Micieli

Las Heras. Santa Cruz. 2018 © Leo Micieli

Las Heras. Santa Cruz. 2018 © Leo Micieli

Las Heras. Santa Cruz. 2018 © Leo Micieli

Las Heras. Santa Cruz. 2018 © Leo Micieli

Route 43 is still ahead, and the pumpjacks at the side of the road.

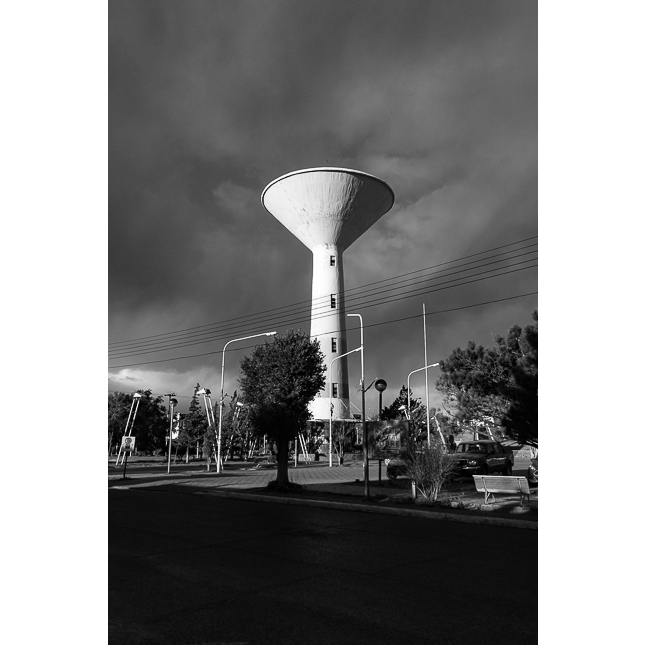

Pico Truncado is the next stop. Its name comes from the Truncado Hill, placed at just a few kilometers. The city, like the whole basin, has no much beauty, but people is very kind and the surroundings are worth to watch.

Truncado Hill. Pico Truncado, Santa Cruz. 2018 © Leo Micieli

Truncado Hill. Pico Truncado, Santa Cruz. 2018 © Leo Micieli

Las Salinas. Pico Truncado, Santa Cruz. 2018 © Leo Micieli

Las Salinas. Pico Truncado, Santa Cruz. 2018 © Leo Micieli

Sierras Blancas. Santa Cruz. 2018 © Leo Micieli

Sierras Blancas. Santa Cruz. 2018 © Leo Micieli

It's a city, 25000 people live there and it has industries, but it's normal to hear about it as a village. Every part of it has a gentle village-like atmosphere, except when notice that air and water are no longer as pure as before.

A metaphor of what is happening not only here but in the whole Patagonia is the wind farm with four turbines which don't work, wasting this way the allmighty wind, this non-polluting and renewable resource that abounds everywhere, capable of twist trunks and blast roofs out, but can't move the propellers.

Wind farm. Pico Truncado, Santa Cruz. 2018 © Leo Micieli

Wind farm. Pico Truncado, Santa Cruz. 2018 © Leo Micieli

The further East, the more problems with water supplying or quality. It's easy to notice it in the taste and smell, and if water is used for 'mates' the yerba becomes bluer after a while. The amount of cancer cases here and in Caleta Olivia, near to Pico Truncado, are concerning. There are no researches neither public nor private about this situation, which causes suspicions due to the obvious incidence of industry in this matter. The probabilities of having medical attention are very low, there are not enough medics for such a high demand. Those who have good health insurances are in a better situation while the rest do what they can, if they can, and long distances complicate the circumstances. Even having medical attention it would be better to prevent it. The lack of reliable data is a barrier in the way to make prevention policies. The question is: if those data were available, is there a real will of make such policies.

Oil and salt. Pico Truncado, Santa Cruz. 2018 © Leo Micieli

Oil and salt. Pico Truncado, Santa Cruz. 2018 © Leo Micieli

Pico Truncado. Santa Cruz. 2018 © Leo Micieli

Pico Truncado. Santa Cruz. 2018 © Leo Micieli

Cement factory. Pico Truncado, Santa Cruz. 2018 © Leo Micieli

Cement factory. Pico Truncado, Santa Cruz. 2018 © Leo Micieli

The city is simple, small houses, a downtown with some stores. In spite of that there's the intention of beautify it with murals or other art works, and the cultural offer is wider than in other places, with artist who come from many parts of the country and other countries too. Old railway buildings, zinc-sheets houses and water tanks towers with the futuristic desing of half of the XX Century.

Pico Truncado. Santa Cruz. 2018 © Leo Micieli

Pico Truncado. Santa Cruz. 2018 © Leo Micieli

Pico Truncado. Santa Cruz. 2018 © Leo Micieli

Pico Truncado. Santa Cruz. 2018 © Leo Micieli

Pico Truncado. Santa Cruz. 2018 © Leo Micieli

Pico Truncado. Santa Cruz. 2018 © Leo Micieli

Pico Truncado. Santa Cruz. 2018 © Leo Micieli

Pico Truncado. Santa Cruz. 2018 © Leo Micieli

Pico Truncado. Santa Cruz. 2018 © Leo Micieli

Pico Truncado. Santa Cruz. 2018 © Leo Micieli

Pico Truncado has the same environmental problems than other cities and near towns, and a priori there's not too much to show, but hidden behind that idea there's more than it is supposed, starting with the warmth of the people I knew here and the strength in a cultural level that emerges from them. Everywhere I find solidarity and generosity, but in this city I was able to notice it abundantly. While doing more kilometers I confirm that this vision is not just personal. Another prejudice that blows up in this trip.

Cinema and Theater of Gas del Estado. Pico Truncado, Santa Cruz. 2018 © Leo Micieli

Cinema and Theater of Gas del Estado. Pico Truncado, Santa Cruz. 2018 © Leo Micieli

Pico Truncado. Santa Cruz. 2018 © Leo Micieli

Pico Truncado. Santa Cruz. 2018 © Leo Micieli

Pico Truncado. Santa Cruz. 2018 © Leo Micieli

Pico Truncado. Santa Cruz. 2018 © Leo Micieli

A little walk of an afternoon by the town of Fitz Roy allows to see how the railway was in other times. Something is preserved, or that's the idea. Though good intentions are not always enough, it's better than not having them, and results are evident.

Like in Puerto Deseado, the end or beginning of this railroad, the old facilities of the train that once crossed these lands are well preserved or restored.

Fitz Roy. Santa Cruz. 2018 © Leo Micieli

Fitz Roy. Santa Cruz. 2018 © Leo Micieli

Fitz Roy. Santa Cruz. 2018 © Leo Micieli

Fitz Roy. Santa Cruz. 2018 © Leo Micieli

Fitz Roy. Santa Cruz. 2018 © Leo Micieli

Fitz Roy. Santa Cruz. 2018 © Leo Micieli

Fitz Roy. Santa Cruz. 2018 © Leo Micieli

Fitz Roy. Santa Cruz. 2018 © Leo Micieli

Having already passed last year by Caleta Olivia and Comodoro Rivadavia, I skip them now and head towards the last town of the Basin on this trip: Sarmiento, called Sarmiento Colony before.

Musters Lake. Sarmiento, Chubut. 2018 © Leo Micieli

Musters Lake. Sarmiento, Chubut. 2018 © Leo Micieli

School No. 14. Sarmiento, Chubut. 2018 © Leo Micieli

School No. 14. Sarmiento, Chubut. 2018 © Leo Micieli

Sarmiento. Chubut. 2018 © Leo Micieli

Sarmiento. Chubut. 2018 © Leo Micieli

Rural landscape is more evident in this town that is still part of the Basin and has part of its people working in oil.

Difference is noticed in the groves, high poplars that skirt the streets and form a shield against the wind, in the farms inside and outside the urban area and the small houses that preserve the air of the first decades of the past century.

Sarmiento. Chubut. 2018 © Leo Micieli

Sarmiento. Chubut. 2018 © Leo Micieli

Sarmiento. Chubut. 2018 © Leo Micieli

Sarmiento. Chubut. 2018 © Leo Micieli

Sarmiento. Chubut. 2018 © Leo Micieli

Sarmiento. Chubut. 2018 © Leo Micieli

Sarmiento. Chubut. 2018 © Leo Micieli

Sarmiento. Chubut. 2018 © Leo Micieli

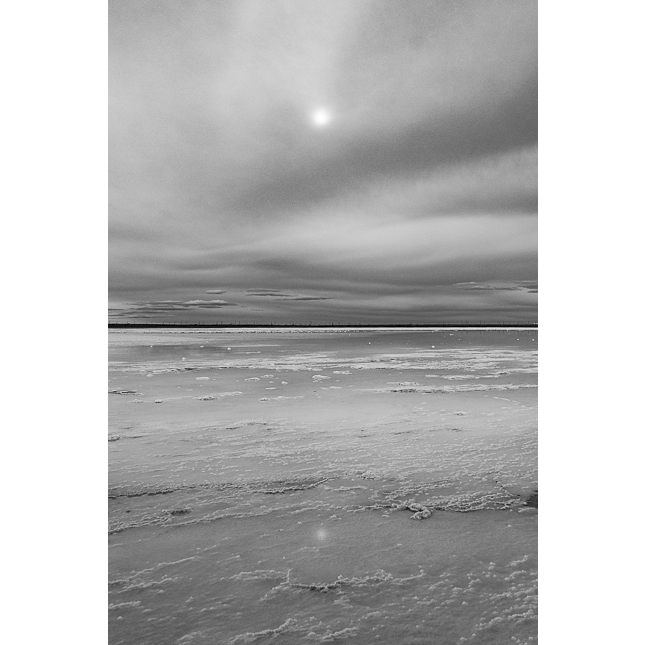

It's placed between two lakes: Colhué Huapi, large but shallow and dried nowadays, and Musters, also large though not as much as Colhué Huapi, and much deeper. Musters Lake is wildly beautiful and in windless days forms a wonderful water mirror. Besides, it's a lake that provides water to other places, Caleta Olivia among them, a city that is located in other province, Santa Cruz.

Musters Lake. Sarmiento, Chubut. 2018 © Leo Micieli

Musters Lake. Sarmiento, Chubut. 2018 © Leo Micieli

Sarmiento. Chubut. 2018 © Leo Micieli

Sarmiento. Chubut. 2018 © Leo Micieli

Sarmiento. Chubut. 2018 © Leo Micieli

Sarmiento. Chubut. 2018 © Leo Micieli

Sarmiento. Chubut. 2018 © Leo Micieli

Sarmiento. Chubut. 2018 © Leo Micieli

Streets are quiet, you want to walk by them all day long. In general, all Patagonia is quiet, but perhaps more here. Or I perceived it so. Even the weather is nice considering the season in which I arrive. Days of 20 degrees, sunny and windless, and in autumn, are almost a miracle. It won't last long because the implacable wind will come sooner or later, but a couple of days like these are more than enough for me.

Also here people have a good mood, inviting, smiling, conveying something that inspires to take it to other people so they can know it.

The town, though part of the oil panorama, grows cherries, strawberries, grapes, cattle. It tends to be less industrial and closer to the ancient human activities which instead of extracting resources from the Earth, produce and renew them. As usual, the mood of the people is determined by the activity they daily develop.

Sarmiento. Chubut. 2018 © Leo Micieli

Sarmiento. Chubut. 2018 © Leo Micieli

Sarmiento. Chubut. 2018 © Leo Micieli

Sarmiento. Chubut. 2018 © Leo Micieli

Musters Lake. Sarmiento, Chubut. 2018 © Leo Micieli

Musters Lake. Sarmiento, Chubut. 2018 © Leo Micieli

Sarmiento. Chubut. 2018 © Leo Micieli

Sarmiento. Chubut. 2018 © Leo Micieli

Sarmiento. Chubut. 2018 © Leo Micieli

Sarmiento. Chubut. 2018 © Leo Micieli

This sub-region of Patagonia is crossed by heavy facts. It's so particular that, without being detailist, between 40's and 50's it was administrated by the military, the so called 'Military Government of Comodoro Rivadavia', with the capital in the homonymous city. Something like the prototype of a province that included the north area of Santa Cruz and the south of Chubut. Both of them were restored to those provinces after. The strong martial character of this region is something that also transcended to the next years.

Oil played before and play now a decisive roll in the San Jorge Gulf Basin. As it uses to be with everything related with the 'black gold', the oil economy goes up and down just like pumpjacks, depending on decisions taken in a handful of places in the World that are not here, making on one hand money to spill out while on the other a panic is produced due to the fear of losing it, or losing what it represents.

Although hypothetical, it's useful to imagine this area within a hundred years, or fifty years, or even less, and doing it widely: environment, resources, work, education, quality of life, health. Concretely, what is happening now after the century that passed since oil was found that December 13rd of 1907. Also, what would have happened if water had sprout out instead of oil. And a last question, not so hypothetical: isn't this obsolete and dark fuel too alike with that obsolete and dark coal brought by Great Britain a century ago?

Musters Lake. Sarmiento, Chubut. 2018 © Leo Micieli

Musters Lake. Sarmiento, Chubut. 2018 © Leo Micieli

BEATRIZ MAZQUIARAN (25/05/2018)

muy buenas fotos leo me encantaron !!!!!!!!!!!

Gracias Bety! Un gusto haberlos conocido, besos grandes!

Julio (31/05/2018)

Leo cuantas anécdotas , vivencias y además hacernos conocer a los lectores las realidades de cada zona recorrida , cosa que supongo la mayoría de los Argentinos ignoramos. Como siempre muy buenas fotografías de las bellezas sureñas.

Gracias! Hay realmente mucho para contar de la Patagonia. Abrazos grandes!

Km 30-100 - First impressions in Patagonian Coast

Km 100-410 - The sea

Km 410-3650 - 'Stop, look, listen'. (Part 1/2)

Km 410-3650 - 'Stop, look, listen'. (Part 2/2)

Km 3650-4190. Puerto Madryn - Puerto Pirámides - Bird Island

Km 4190-4710. Trelew-Comodoro Rivadavia-Caleta Olivia

Km 4710-5750. Coast of Santa Cruz. (Part 1/2)

Km 4710-5750. Coast of Santa Cruz. (Part 2/2)

Km 5750-6960. Tierra del Fuego

Km 6960-8800. West of Santa Cruz.

Km 8800-9670. San Jorge Gulf Basin.

Leave a Reply